If various facial features were to be associated with particular countries, Greece would surely get the nose. But – despite having given the name to one of the most popular nose shapes, many Greeks seem to dislike their own.

Over 15,000 plastic surgeries are performed each year in Greece, with nose jobs being the most popular type of cosmetic intervention in the country, the Focus News Agency wrote in November, citing a News In publication.

It mentioned data by the World Plastic Surgery Organisation, according to which Greece is in 18th position among 42 countries in terms of the number of plastic surgery interventions carried out per year, coming before countries such as England, Italy and Denmark.

The most popular cosmetic alteration among Greeks is supposedly the nose job, or rhinoplasty, which – incidentally, finds its name origins in Greek (from rhinos – ‘nose’ and plassein – ‘to shape’).

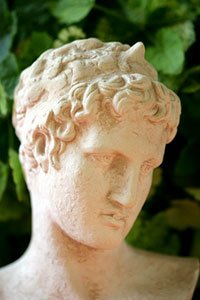

Although nose shapes ‘categorisations’ are far from uniform, ‘Greek’ is quite a constant category used to describe noses that are straight from the top to the botton, when viewed from profile. Another popular category is the Roman nose, in which the nose bridge had a bump.

The origin of these classifications is not entirely clear – while some claim Greek noses are in fact possessed by many – if not all, Greeks, and Roman ones – by Italians, a more reasonable explanation may be that these descriptions have their roots in classical ancient art, rather than stem from real people’s physical characteristics.

The origin of these classifications is not entirely clear – while some claim Greek noses are in fact possessed by many – if not all, Greeks, and Roman ones – by Italians, a more reasonable explanation may be that these descriptions have their roots in classical ancient art, rather than stem from real people’s physical characteristics.

“May not the straight nose have been a conventionality of art, just as certain other peculiarities of Greek sculptural anatomy are unnatural conventionalities?,” the New York Times asked in an article from December 4, 1897.

But if ancient art stands behind the coining of the term, then it is ironic that many Ancient Greek sculptures – even ones that are well-preserved, have missing noses, making it difficult to assert whether the bridge is straight or with a bump.

A typical example of a Greek nose, according to a source, is neither Ancient Greek nor Roman, but rather the nose of what may be the best-known Renaissance sculpture, Michelangelo’s David. Ironically, when the statue was unveiled in 1504, David’s nose was considered to be too big. According to historical accounts, after a Florentine leader voiced his concern over the size of the nose, Michelangelo climbed up, pretended to chisel at it, allowing just enough dust to fall to make believe he had changed its shape. When he came down, the critic said the statue was much better.

Either way, to return to the Greeks that are unhappy with the shape of their nose, it may be useful for them to consider the advice on how to read character from features, offered by America’s original beauty authority, the Victorian woman Harriet Hubbard Ayer, who lived in the second part of the nineteenth century. In her A Complete and Authentic Treatise on the Laws of Health and Beauty, published in 1902, she wrote:

“The Greek nose, which forms a straight line from base to tip, is considered the perfect nose. It indicates a gentle, peaceable nature, with a love of the beautiful–of the arts and of home. The Greek nose does not belong to the most forcible type of womanhood, but Greek-nosed women rarely are quarrelsome, and with a good, moderately large mouth, a Greek-nosed woman will usually prove a treasure.”